Thumb Spikes: What Are They Good For?

When you ask people to name a dinosaur, the first ones that come to mind are probably genera such as Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus, and the like. However, if you had asked this question among the highbrow scientists of 1840s London, the answer would be confined to Megalosaurus, Hyaleosaurus, or Iguanodon. The reason for this is simple: these were the very first animals used to create the group “Dinosauria” in 1842. In those early dinosaur days, very little material was known. They were all interpreted as lumbering, quadrupedal giant lizards with rhino- or elephant-like bodies. Take Iguanodon, for instance. This generic name means “iguana tooth,” a reference to the observation that its teeth, which was the first Iguanodon material to be studied, looked like that of an iguana’s but much larger. It comes as no surprise, then, that early interpretations of Iguanodon looked like a lizard-rhino hybrid, even after more fossils were discovered.

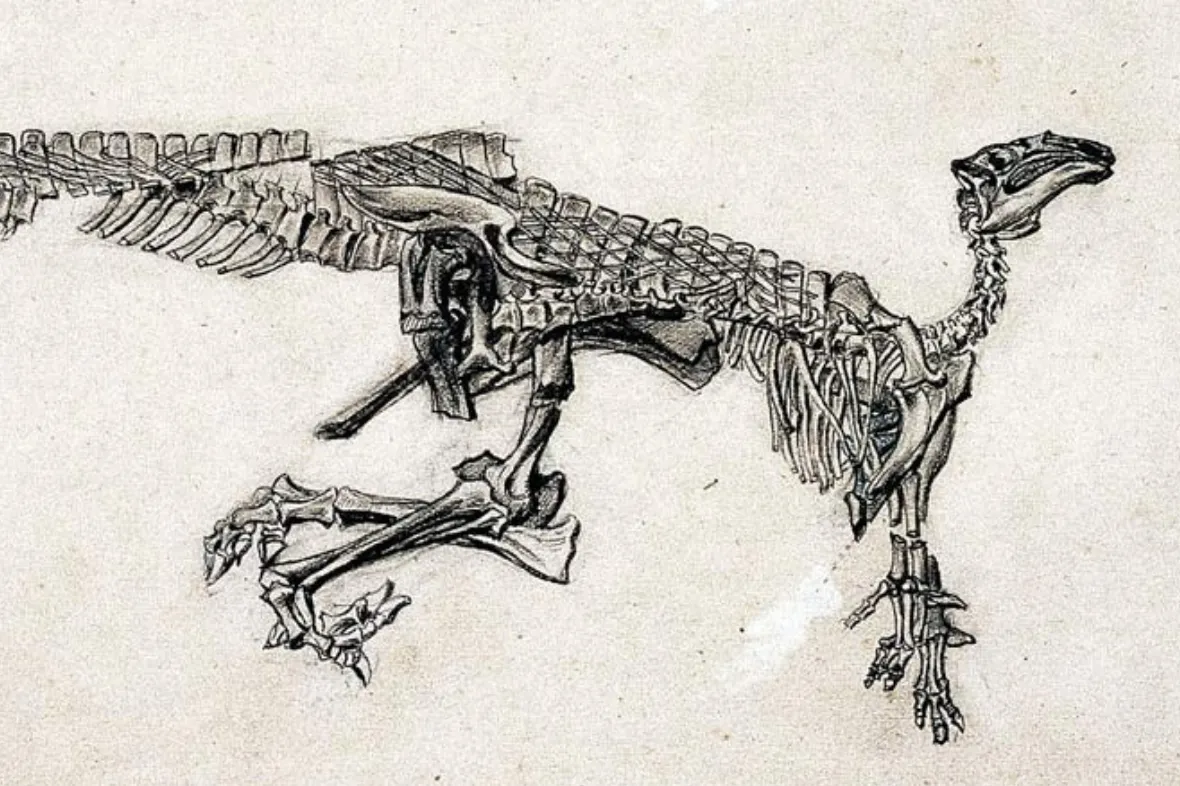

One such Iguanodon fossil was that of a sharp spike. Originally, this bone was interpreted to be a nose horn, as is evidenced by common reconstructions of the time period. However, in the 1870s, lots of new fossils representing multiple individuals were found in Belgium, revealing the true nature of Iguanodon’s spike. In reality, Iguanodon possessed two spikes, and neither were on the head. Rather, each thumb terminated in spikes. Further, a much sleeker Iguanodon body plan was revealed. Already, the understanding of Iguanodon was catapulting to modern levels, though contemporary reconstructions were still supremely outdated compared to present standards. As more of Iguanodon was revealed, questions still abounded, specifically regarding said spikes.

Even with today’s well-informed Iguanodon re-creations, the purpose of the spikes remains a mystery. Were they used for warding off predators? To strip foliage from branches? Or perhaps to fight among themselves? While this question may not be definitely answered, examining close relatives and even modern birds may help to elucidate the true nature of the spikes.

Iguanodon previously had many random species, as any dinosaur that looked remotely similar was lumped into the genus for many decades. Some notable examples include Mantellisaurus, Dakotadon, Hypselospinus, and Altirhinus. The species still assigned to Iguanodon proper are I. bernissartensis and I. galvensis. All of these genera are all ornithopods, with Mantellisaurus joining Iguanodon in iguanodontidae. Also within this group is Lurdusaurus arenatus, which may help provide some insight on Iguanodon’s thumb spikes. L. arenatus was described as “massively-constructed” in the paper describing the genus, published in 1999 by Philippe Taquet and Dale A. Russell. According to Taquet and Russell, the forearm of the animal was “powerfully” built with a massive thumb spike, larger than that of Iguanodon. Their interpretation is that this “mace-and-chain” arm was perfectly suited for self-defense from would-be predators. Since the two genera are fairly close relatives, it is enticing to apply this conclusion to Iguanodon thumb spikes.

A major caveat to doing so, however, is that Lurdusaurus is a very unique dinosaur that likely filled a different ecological role in its North African home. First, it is very robust, as even its pelvis and chest were larger than those of Iguanodon. Second, its shorter limbs and rotund chest may have signified a semi-aquatic lifestyle with comparisons to modern-day hippos. Iguanodon, meanwhile, was almost definitely a terrestrial animal. As such, it may be difficult to conclude that the pair are the same in terms of thumb-spike behavior given their vastly different body plans.

Other, more distant relatives of Iguanodon may support the same idea that Lurdusaurus does while also establishing another possibility. While not exactly a thumb spike, many species of the present-day dinosaurs, birds, have spurs used for different combative purposes. One example cited by Austin L. Rand is the swan, which sometimes uses its spur to fight off other bird species. However, most of the examples of bird spur usage is in fighting within the same species, which raises a new hypothesis: the thumb spikes of Iguanodon were used in some form of sexual selection. G. W. H. Davidson published an analysis on spurs in ground-dwelling galliforme birds in 1985. In his paper, he discussed how the spurs of the male birds in some species were present to seemingly act as an indicator of fighting prowess towards foes. This display is to intimidate the rival and avoid physical confrontation. Another purely visual usage is towards females, where it may provide prospective mates with a means of measuring genetic quality, where larger spurs are “better.” These possible reasons are referred to as “spurs as advertisements” by Davidson. Perhaps Iguanodon’s spikes were used in a similar fashion, to act as a visual cue to both enemies and possible mates.

Davidson also speaks on the physical usage of spurs. They can be used both to fight rival males or in territorial disputes. Notably, Davidson mentions that females of some galliforme species also have spurs. This adaptation is generally seen in monogamous species so that both individuals of the pairing can engage in territorial disputes against challengers together. Looking back at Iguanodon, it is important to note that they are interpreted as not being herd animals. This view can then be extrapolated into positing that Iguanodon was monogamous and that both male and female individuals possessed the spikes for territorial purposes.

Of course, this conclusion includes a bit of educated guessing and assumes a greater similarity between bird spurs and thumb spikes. According to Davidson, bird spurs are very derived, evolving in birds relatively recently. They are not an ancient feature descended from some common ancestor with Iguanodon that had some spur-thumb spike hybrid. As such, the conclusion that Iguanodon spikes were for intraspecific conflict rests on the notion that its thumb spikes and bird spurs are examples of convergent evolution. Convergent evolution is the process in which similar features evolve independently from each other in different lineages, such as bat wings compared to bird wings. In reality, most bird spurs are found on the hind legs of the bird, with only some species possessing spurs on their wings. However, it is still a valid hypothesis in light of the lack of direct fossil evidence.

One final possibility to be explored here is the idea that the spikes were used to strip foliage from trees or to simply aid in pulling branches down to mouth height. Iguanodon is known to be herbivorous, something that was known since its discovery. Iguanas are herbivorous, so early scientists correctly assumed the same of the dinosaur based off of the similar tooth shape. Further, Iguanodon’s posture may have dictated what it ate. Originally interpreted as a sluggish quadruped, later reconstructions depicted Iguanodon as a purely bipedal animal complete with a dragging tail. Modern consensus has adopted a mixture of the two ideas, but combined with more contemporary principles. While mainly an active quadruped, Iguanodon could likely rear up and walk on two legs when necessary; its front legs are shorter than those in the back. While this system affects its locomotion, it may also help paleontologists understand the animal’s diet. It may have used its bipedal capabilities to reach leaves growing at a greater height than the other herbivores of its environment, such as the smaller Mantellisaurus. An additional aid, as alluded to earlier, may have lied in the thumb spikes. By reaching its arms up and using its thumb to strip foliage from tree branches, a feeding Iguanodon may have been able to reach even higher. This use would have greatly expanded the amount of foliage Iguanodon could eat, while also further distancing themselves from other local herbivores.

It may seem impossible to prove this hypothesis, and it well may be. However, tooth fossils from the Late Jurassic have actually been examined for chemical signatures that provide clues as to what certain dinosaurs ate. According to researchers from the University of Texas at Austin, a microscopic analysis of the teeth of the herbivorous dinosaurs Camptosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus. From the analysis, they were able to determine that Camptosaurus ate mainly soft plant parts, Camarasaurus ate mainly conifers, and Diplodocus mainly consumed low-lying ferns and horsetails. This knowledge may help in multiple ways; first, an analysis of Iguanodon teeth may yield information on what type of plant parts they ate, which may be able to be placed at a certain average height. If this estimated height is higher than a bipedal Iguanodon, they may have used their spikes to close the gap. Second, if such an analysis could be conducted on the spikes themselves, scientists may be able to determine if they handled foliage with any consistency. It is important to note that these are hypothetical extensions of the UT Austin research, and all such analysis may result in is further understanding Iguanodon’s diet, not how it used its spikes.

Indeed, unless a contemporary carnivorous skull is discovered with an Iguanodon spike through it, the exact usage may always be a mystery. It may be one of the ideas discussed above, a mixture of all three, or maybe even something completely different. Regardless, the thumb spike remains one of the most endearing and recognizable dinosaur features, and Iguanodon maintains its status as one of the earliest known and most important dinosaur discoveries.

References:

Black, Riley. “A Mysterious Thumb.” Smithsonian Magazine, 27 Dec. 2011, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/a-mysterious-thumb-12453139/.

“Clues for Dinosaurs’ Diets Found in the Chemistry of Their Fossil Teeth.” Utexas.edu, Jackson School of Geosciences, 24 July 2025, www.jsg.utexas.edu/news/2025/07/clues-for-dinosaurs-diets-found-in-the-chemistry-of-their-fossil-teeth/.

Davison, GWH. “Avian Spurs.” Journal of Zoology, vol. 206, no. 3, 1 July 1985, pp. 353–366, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb05664.x.

Green, Jamie. “Iguanodon | EBSCO.” EBSCO Information Services, Inc. | Www.ebsco.com, 2023, www.ebsco.com/research-starters/earth-and-atmospheric-sciences/iguanodon.

McDonald, Andrew T., et al. “New Basal Iguanodonts from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs.” PLoS ONE, vol. 5, no. 11, 22 Nov. 2010, p. e14075, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014075.

Reginald Walter Hooley. “On the Skeleton of Iguanodon Atherfieldensi Sp. Nov., from the Wealden Shales of Atherfield (Isle of Wight).” The Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, vol. 81, no. 1-4, Mar. 1925, pp. 1–61, https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.jgs.1925.081.01-04.02.

Sargeant, William A.S., et al. “The Footprints of Iguanodon: A History and Taxonomic Study.” Ichnos, vol. 6, no. 3, 1 Dec. 1998, pp. 183–202, https://doi.org/10.1080/10420949809386448. Accessed 24 Apr. 2023.

Taquet, Philippe, and Dale A. Russell. “A Massively-Constructed Iguanodont from Gadoufaoua, Lower Cretaceous of Niger.” Annales de Paléontologie, vol. 85, no. 1, Jan. 1999, pp. 85–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0753-3969(99)80009-3.

Picture Sources:

https://prehistoricbeastoftheweek.blogspot.com/2015/11/lurdusaurus-beast-of-week.html

https://cpdinosaurs.org/visit/statue-details/iguanodon

https://sedgwickcommon.co.uk/reducing-cockerels-spurs-in-steps/

https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/the-discovery-of-iguanodon.html

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/200-years-of-iguanodon-focus

https://dinotoyblog.com/iguanodon-ukrd/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iguanodon_paleoart_2025.png

Photo of the three Iguanodon figures by Richard Gutierrez